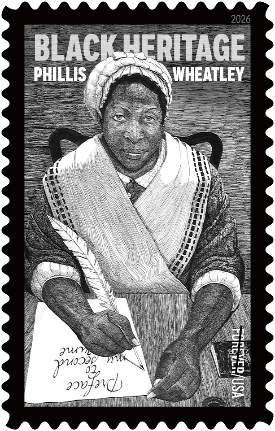

Today, the US Postal Service launched a stamp in honor of the great Phillis Wheatly, my shero, the first African American woman to publish a book, hers being a book of poetry. I take this occasion to launch my new podcast—What Would You Do For Democracy?—the Evolution of the Revolution, which you will find next week wherever you get your podcasts. I’ll post the links next week as we move the podcast technology.

This podcast is the evolution of my Threshold to Valley Forge podcast, which is about my award-winning book, Threshold to Valley Forge: The Six Days of the Gulph Mills Encampment. My new podcast ties the people, places, and activities of the Gulph Mills Encampment directly to the question What Would You Do for Democracy, which is the question that I asked myself as I felt the extreme personal sacrifice of the soldiers, officers, their families, and all citizens of the new United States, when I wrote the book. I posted this question prominently on my website, and I ask attendees to think about this question as they listen to my presentations and speeches. This blog post is essentially the last episode of my Threshold to Valley Forge podcast (link below to it on Spotify).

The What Would You Do for Democracy podcast will start with a look into the people I talk about in my book. I will dive deep into their backgrounds and contributions. I will tie their lives and contributions to what is happening today. I will often have guests who will provide special insights into that person or situation as they talk about what they are doing for democracy. And, I will end every episode with the question—what will you do for democracy?

So, let’s dive into today’s episode. I have a special affinity for Phillis Wheatley. As a writer and book publisher myself, with my company The Elevator Group, I feel close to Wheatly on that basis alone. I know how hard it is to write and to publish a book, especially as an African American woman, her being an enslaved one for half of her life. When I could not find a publisher for my first book, the novel, Chasing the. 400, I published it myself. Then I went on to publish 15 other books and eight other authors. Wheatly inspired me.

Also, I was a journalism major at Howard University School of Communications. So, again, I was drawn to Wheatly’s accomplishments and courage as a writer.

I first learned about Wheatly during my freshman year at Howard when I lived in Wheatly Hall, named after her. What a legacy that was impressed on my mind as soon as I started college.

And, as someone who has written extensively about the Revolutionary War since 2011, I feel close to Wheatly’s writings about the same. She lived during that time period. She wrote poems for General George Washington, and she even corresponded with and met him. She took a stand for liberty and for the Commander-in-Chief, in spite of, or because, she knew what it was to be enslaved as she was. Like many former enslaved persons, she hoped that other enslaved persons would, too, be free.

I start my book with a quote from Wheatley’s October 26 1775 letter to Washington. That quote is:

Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side,

Thy ev’ry action let the goddess guide.

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine,

With gold unfading, Washington! be thine.

The Poem in full is below.

So let’s do a deep dive into the life of Phillis Wheatly. George Washington’s Mount Vernon does an excellent job of providing information about Wheatley, as well as an analysis of her poems, in great detail. I have highlighted some of that information below.

The Remarkable Legacy of Phillis Wheatley

Exploring Her Impact, Challenges, and Connection to George Washington

The Importance and History of Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley stands as one of the earliest published African American poets and a remarkable figure in American literary history. Born in West Africa around 1753, she was kidnapped and brought to Boston, Massachusetts, aboard the slave ship the Phillis at about age seven or eight. Purchased by the Wheatley family in 1761, Phillis was taught to read and write—a rare occurrence for an enslaved person in 18th-century America. Her extraordinary aptitude for poetry became evident in her childhood years, and she soon began composing verses that would earn her international recognition. Her earliest published poem is “On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin,” which appeared in the Newport Mercury newspaper on December 21, 1767. Written when she was approximately 13 or 14 years old, the poem recounts a harrowing story of sailors escaping a disaster at sea.

Breaking Barriers as a Writer

Wheatley’s accomplishments are especially significant given the social and historical context in which she lived. In an era when enslaved people were denied basic human rights and education, Wheatley’s literary achievements challenged the prevailing beliefs about race and intellect. Wheatley was taken to London by the Wheatley family in early 1773. While there, Wheatly met with Ben Franklin. On July 7, 1773, Franklin wrote to a friend, Jonathan Wiliams, about Wheatley—“Upon your recommendation I went to see the black Poetess and offer’d her any Services I could do her. Before I left the House, I understood her Master was there and had sent her to me but did not come into the Room himself, and I thought was not pleased with the Visit. I should perhaps have enquired first for him; but I had heard nothing of him. And I have heard nothing since of her.

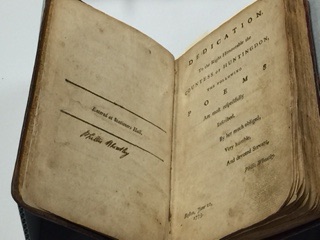

In October 1773, upon her death, Wheatly’s enslaver, Susanna Wheatley, freed Wheatly. Wheatley’s first and only published book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was released in London in 1773, when she was about 20 years old. The collection includes 39 poems, primarily written in neoclassical style, reflecting themes of religion, morality, and freedom. Notable works from this collection include “On Being Brought from Africa to America,” “To the University of Cambridge, in New England,” and “On the Death of the Rev. Mr. George Whitefield.” This book made her the first African American and one of the first women in the United States to publish a book.

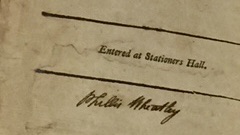

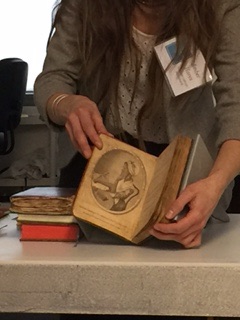

I was honored and thrilled to hold the first edition, signed copy of Wheatley’s book in my hands right before it was donated to the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia, where it is now on display.

White Skepticism and the Quest for Validation

Despite her talents, Phillis Wheatley faced intense skepticism from white society. Many white men doubted that an enslaved Black woman could produce poetry of such sophistication. To address these doubts, Wheatley was subjected to an examination in 1772 by a group of 18 prominent Boston men—including politicians, clergymen, and scholars such as John Hancock—who questioned her about her work. This panel concluded that Wheatley was indeed the author of her poems, and their signed attestation was included as a preface to her book. This experience highlights the racial prejudices of the time and the extraordinary hurdles Wheatley had to overcome simply to be recognized for her talent.

Phillis Wheatley and George Washington

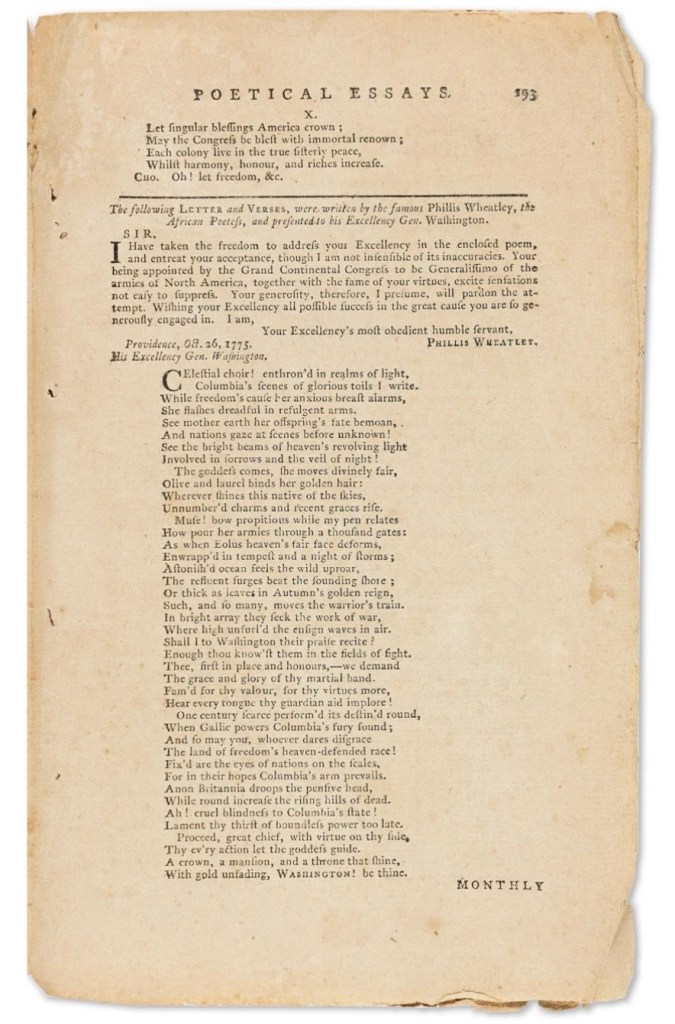

Wheatley’s influence extended to the leaders of her era, notably George Washington. In 1775, she wrote the poem “To His Excellency General Washington,” which praised his leadership during the American Revolution and presented him as a champion of liberty. In Wheatley’s October 26, 1775 letter to Washington, she wrote, “I have taken the freedom to address your Excellency in the enclosed poem.” She continued, “though I am not insensible of its inaccuracies, your being appointd by the Grand Continental Congress to be Generalissimo for the armies of North America, together with the fame of your virtues, excite sensation not easy to suppress.”

Washington tucked the letter away with a mound of other correspondence and documents.

In February 10, 1776, Washington again came across Wheatley’s letter under a pile of papers. At the end of a long letter to Colonel Joseph Reed of Pennsylvania, Washington wrote, “I recollect nothing else worth giving you the trouble of, unless you ca be amused by reading a Letter and Poem addressed to me by Mrs or Miss Phillis Wheatley—in searching over a parcel of Papers the other day, in order to destroy such as were useless, I brought it to light again—at first, With a view of doing justice to er great poetical Genius, I had a Mind to publish the Poems, not knowing whether it might not be considered rather as a mark of my own vanity than as a Compliment to her I laid it aside till I came across it again in the manner just mentioned.”

Washington wrote Wheatley on February 28, 1776. His letter reads:

To Philis Wheatley.

Mrs Phillis Cambridge, February 28, 1776.

Mrs Phillis,

Your favour of the 26th of October did not reach my hands ’till the middle of December. Time enough, you will say, to have given an answer ere this. Granted. But a variety of important occurrences, continually interposing to distract the mind and withdraw the attention, I hope will apologize for the delay, and plead my excuse for the seeming, but not real, neglect.

I thank you most sincerely for your polite notice of me, in the elegant Lines you enclosed; and however undeserving I may be of such encomium and panegyrick, the style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your great poetical Talents. In honour of which, and as a tribute justly due to you, I would have published the Poem, had I not been apprehensive, that, while I only meant to give the World this new instance of your genius, I might have incurred the imputation of Vanity. This, and nothing else, determined me not to give it place in the public Prints.

If you should ever come to Cambridge, or near Head Quarters, I shall be happy to see a person so favourd by the Muses, and to whom nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations. I am, with great Respect, Your obedt humble servant,

G. Washington

Impressed by her work, Washington invited Wheatley to visit him at his headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in March 1776. Their meeting was a testament to Wheatley’s growing reputation and the respect she garnered from some of the most influential figures in American history. Washington later expressed his gratitude in a letter, acknowledging her poetic tribute.

Colonel Reed, however, published Wheatley’s poem in the Virginia Gazette on March 30, 1776. Mt. Vernon records, “Reed published the poem in the Virginia Gazette on March 30, 1776, just a month after Thomas Paine’s Common Sense ignited the sprit of colonial America. Paine, perhaps wishing to be inclusive to Wheatly’s revolutionary rhetoric, republished the poem with Reed’s headnote that emphasizes Wheatley’s racial identify: ‘The following letter and verses written by the famous Phillis Wheatly, the African Poetess, and presented to His Excellency Gen. Washington.’ Paine included the poem in the April 1776 edition of his Pennsylvania Magazine.

Wheatley wrote a second volume of poems, but sadly, that was not published before her death in 1784 at age 31. She died in poverty, and all of her children from her marriage to John Peters died in infancy.

Her Enduring Legacy

Phillis Wheatley’s legacy is one of resilience, intellect, and artistic achievement. She broke through immense barriers to become a published poet, challenged the racist assumptions of her time, and influenced major figures in early American history. Although she struggled to find a publisher for a second volume of poetry during her lifetime, many of her poems survived in newspapers and private letters. Today, she is celebrated not only as a literary pioneer but also as a symbol of the power of education, the importance of voice, and the enduring struggle for equality. Her life and work continue to inspire readers, writers, and advocates for social justice across generations.

Peace—

Sheilah

Enclosure

Poem by Phillis Wheatley (in letter to George Washington)

Celestial choir! enthron’d in realms of light,

Columbia’s scenes of glorious toils I write.

While freedom’s cause her anxious breast alarms,

She flashes dreadful in refulgent arms.

See mother earth her offspring’s fate bemoan,

And nations gaze at scenes before unknown!

See the bright beams of heaven’s revolving light

Involved in sorrows and the veil of night!

The goddess comes, she moves divinely fair,

Olive and laurel binds her golden hair:

Wherever shines this native of the skies,

Unnumber’d charms and recent graces rise.

Muse! bow propitious while my pen relates

How pour her armies through a thousand gates:

As when Eolus heaven’s fair face deforms,

Enwrapp’d in tempest and a night of storms;

Astonish’d ocean feels the wild uproar,

The refluent surges beat the sounding shore;

Or thick as leaves in Autumn’s golden reign,

Such, and so many, moves the warrior’s train.

In bright array they seek the work of war,

Where high unfurl’d the ensign waves in air.

Shall I to Washington their praise recite?

Enough thou know’st them in the fields of fight.

Thee, first in place and honours,—we demand

The grace and glory of thy martial band.

Fam’d for thy valour, for thy virtues more,

Hear every tongue thy guardian aid implore!

One century scarce perform’d its destined round,

When Gallic powers Columbia’s fury found;

And so may you, whoever dares disgrace

The land of freedom’s heaven-defended race!

Fix’d are the eyes of nations on the scales,

For in their hopes Columbia’s arm prevails.

Anon Britannia droops the pensive head,

While round increase the rising hills of dead.

Ah! cruel blindness to Columbia’s state!

Lament thy thirst of boundless power too late.

Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side,

Thy ev’ry action let the goddess guide.

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine,

With gold unfading, Washington! be thine.

Leave a comment