[add video]

Yes, the Battle of Matson’s Ford, December 11, 1777! I don’t recall ever being taught this while I was a student in Upper Merion School District, nor heard about this battle while I grew up in Gulph Mills, on Rebel Hill, which intersects Matson’s Ford Road, which starts where the old Matson’s Ford was located. The Ford was a low point in the Schuylkill River that allowed people to cross the river back in the day before there were major and well-built bridges.

But the Battle of Matson’s Ford occurred just as General George Washington had assembled the main body of the Continental Army, about 11,000 soldiers, to march from their encampment in Whitemarsh on the east side of the Schuylkill River to their encampment in Gulph Mills, on the west side of the Schuylkill River.

Brigadier General James Potter and about 1000 members of the Pennsylvania Militia were the first to leave the Whitemarsh Camp. Gen. Washington ordered them to create three pickets, or small groups to cover the distance between the Continental Army crossing at Matson’s Ford and the British stationed in the center of the city of Philadelphia and to alert the main army if any British advanced. Potter stationed militia troops at three points along the Schuylkill—Middle Ferry, in West Philadelphia near Market Street; at the Black Horse Inn at City Line and Lancaster Road, also in West Philadelphia/Lower Merion Township; and at Harriton House, in Lower Merion Township, the plantation of Charles Thompson, Secretary of the Continental Congress, which had moved to York, Pennsylvania after the British captured Philadelphia in September 1777.

The soldiers at Middle Ferry were surprised to see a mass of British soldiers marching towards them and the rest of the army. Unbeknownst to Potter and Washington, British General Lord Cornwallis was out leading a party of some 3000 British soldiers who were foraging—finding and taking food and supplies from local residents. A few militia soldiers then rode towards Potter, who had stationed himself at the third picket, at Harriton House. As the British started marching up the Lancaster Road and the Old Gulph Road, Potter’s militia engaged the British in battle. But, because they were vastly outnumbered, Potter’s militia hastily retreated from one picket and from one high hill to another, in danger and confusion, until they ended up back at Matson’s Ford.

At the same time, General John Sullivan had led two divisions of the Continental Army across the bridge of wagons that the army had strung together to use as a bridge across the Matson’s Ford. Before any more of the army could cross, Sullivan and his forces were surprised to see hundreds, maybe thousands, of British soldiers on the high Conshohocken Hills at Matson’s Ford, watching them cross. Sullivan panicked and, thinking that the entire British Army was out ready to battle with the entire Continental Army, called the soldiers to come back, destroying the wagon bridge behind them. Gen. Washington was called to survey the situation. He determined that the British soldiers looked like a large foraging party, not a party that was part of an attack. While some soldiers were sent out to watch the British soldiers’ movements, Washington ordered the rest of the army to march a few miles further down the east side of the Schuylkill to the Swede’s Ford, in present day Norristown/Bridgeport, to wait to cross the next day.

Potter recorded about 20 of his soldiers taken prisoner, 20 wounded, and five or six killed. He said that the British suffered worse. Potter felt that the militia could have done more to harm the British if General Sullivan had supported them in the battle instead of retreating back across the Matson’s Ford. Gen. Washington commended Potter for his actions and that of the militia that day. Several soldiers and their surviving families mention their injuries, deaths, and service in the Battle of Matson’s Ford in their applications for Revolutionary War Pensions. I include a lot of original description from soldiers in the Battle of Matson’s Ford in my book.

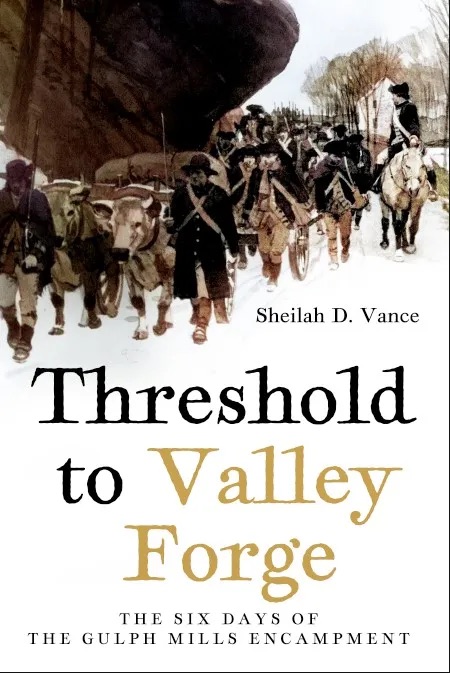

The British soldiers who were foraging were apparently ruthless in their treatment of the Gulph Mills residents. You can see more in my book, Threshold to Valley Forge: The Six Days of the Gulph Mills Encampment.

Check back tomorrow for the march to Gulph Mills.

Best,

Sheilah Vance

Leave a comment